What are (and aren't) organisms!?

Most of this can probably be found in a better manner here. Unsure if majority of these concepts actually provide enough (if any, in some cases) value.

It is often said that organisms perceive a certain part of their environment, what is called the organism’s umwelt. In a sense, what organisms perceive of the world is a reflection of their constraints. What is frequently left underexplained (if not at times unexplained) is which general characteristics differentiate organisms from other physical systems, and what (and what for) is “perceive” as referred previously.

This discussion goes over some remarks on trying to contexualize some of Howard Pattee’s work, which falls under the label of physical biosemiotics, with some of Robert Rosen’s which can be broadly put under the label of relational biology. As I hope it will be perceptible over this discussion, both approaches have large intersections with respect to each other, and have some offspring niche fields today. The former emphasizes organisms as having symbolic controls over matter, having syntactic and semantic relations contextualized with respect to the autonomous system (the organism), and highlights the epistemological limitations always present with these. The latter emphasizes that what makes organisms different from other physical systems is their organization (putting it as a categorical difference in terms of complexity, in contrast to a mere quantitative gradient-like one), as is aswell common in organizational approaches in biology, which take the same idea into account. These stress that the weight is on the relations between the constraints of a system, and not necessarily on the constraints themselves. Majority of these approaches point to the necessity of a system to regenerate the constraints which make it self-organizing, from within its own organization, for such system to be classified as autonomous. Afterall, from the infinitude of dynamical systems that we find in Nature which have some self-organizing capacity, only a few don’t dissipate away and actually maintain such capability. Only a few can be said to be constituted by coupled self-organizing processes which compensate for each other’s dissipative tendencies. Only a few can be said to get progressively better at this. These systems are organisms.

Overall, this is mostly a discussion to try to sort out some confusion in my head about these themes, and as such I hope it has some coherent structure.

Contents

- What are constraints?

- Biological organization as self-constraint

- (Very) brief introduction to (M, R) and (F, A)-systems

- A (very) brief detour into Deacon’s autogen

- What are symbols and what are they for?

- A second look at von Neumann’s self-replicating automata (Rosen’s paradox and the necessity of rate-independent constraints)

1. What are constraints?

Very generally, constraints are physical objects which reduce the number of degrees of freedom available to the system being constrained. We fundamentally associate these to alternative descriptions of the system, that is put in place with laws of motion which are considered to be inexorable from a metaphysical standpoint. Constraints appear out of necessity to simplify the description of said system ignoring selectively some of the detailed dynamics, and as such what constitutes a constraint very much depends on the scale of our description. These readily show themselves as boundary conditions on a system [1-5, 9, 10, 12, 13]. And before continuing, I think it’s useful to consider the following [1]:

But now we are speaking as an outside observer who chooses his descriptions quite subjectively for the purpose of simplifying a problem he wishes to solve or for providing a simple function by a clever use of controls. Living systems on the other hand are created by their constraints and function quite independently of the biologist or physicist who studies them. How do spontaneous constraints arise in matter? Or more exactly, how do we recognize inherent constraints which have evolved autonomously, rather than from the observer’s search for simplification or control? How do we distinguish the living system’s rules and functions from our subjective attempts to describe such enormously complex systems?

There’s always a subject and an object side to this discussion [4] which is not reconcilable in its totality. I hope its clear when I’m referring to the subject and object sides, and when in some scenarios I can’t avoid the mixing of both. Afterall, given that these approaches are trying to describe a bit of what organisms are and how they might know a world, they invariably can’t shy away from putting some light on how us ourselves do it [6].

And it is regarding this context, with the necessity of separation between initial conditions (including boundary conditions, both of which necessarily require measurement) and laws of motion, that people generally assert that we’re still very much under the Newtonian paradigm [not exhaustive; 4, 11, 12]. (Un)fortunately in biology, the “weight” is largely on the former.

1.1 What are rate-dependent, rate-independent, holonomic and non-holonomic constraints?

Rate-independent constraints are usually associated to stable, energy-degenerate and equiprobable structures like linear polymers. For instance, we say that the base in a nucleotide minimally affects the stability of the phosphodiester bond being formed, such that multiple configurations of these polymerized monomers are going to have similar energies. Nonetheless, one shouldn’t think of linear polymers as the only structures which might have these properties. As long as energy-degeneracy is present, other structures are probably also plausible (e.g. plane-like structures). As we will see later, rate-independent constraints are usually associated to symbols, being their material symbolic vehicles (but only when in the context of an autonomous system, or of another system which serves as an extension of such). Rate-dependent constraints, on the other hand, represent the cases where there’s no such stability, thus being largely affected by the system’s dynamics. Of course, rate-(in)dependence is on a spectrum, which also fundamentally depends on our scale of description of said constraints [55]:

This sharp conceptual distinction I have made between rate-dependent and rate-independent processes can of course be challenged on the same grounds that the distinction between reversible and irreversible phenomena are challenged. For example, behavior that is reversible in a system with a small number of particles will appear as irreversible if one has a large number of particles (e.g., P. & T. Ehrenfests’s urn model). From this type of model it can be argued that reversibility and irreversibility are not sharp distinctions but only a matter of degree, the microscopic reversible description being the more objective (i.e., obeying the laws of motion), and the irreversible description being more subjective (i.e., depending on the observer’s information about the system). In a similar way it can be argued that the rate-dependent microscopic laws are the objective reality and the rate-independent measurement constraints are only a practical, subjective simplification of systems with many degrees of freedom.

Additionally, the uses of “objective” and “subjective” here are presumably meant to indicate the complementarity of descriptions necessary to explain a phenomena, with these ones being irreducible to each other, in no way being meant to be interpreted as materialistic naïve [56]. Even in the case of the detailed dynamical description, we are still the ones choosing which observables enter as state-variables in the corresponding formalism. Furthermore, it should be noted that eventhough rate-independent constraints can always be described by rate-dependent ones at the dynamics level, and the reverse not being necessarily the case [5], this in no way implies a greater “fundamentality” to a more detailed description. This assertion like others, is a metaphysical assumption. With that said, as we’ll see later, there’s some importance to rate-independent constraints, and to how rate-dependent ones come to form relations with these.

Also and very briefly, holonomic (integrable) and non-holonomic (non-integrable) constraints [12-14, 5] are respectively described by restrictions on configuration (usually generalized coordinates respective to a set of particles in analytical mechanics, but can presumably be extended to an arbitrary set of state variables) and by additional restrictions on the derivatives of these (generalized velocities, or the corresponding derivatives of the state variables chosen), which result in restriction of motion. These latter constraints are deemed as context-dependent [3] and are very common in organisms. As Pattee writes [4]:

The characteristic property of all these non-holonomic structures is that they cannot be usefully separated from the dynamical system they control. They are essentially non-linear in the sense that neither the dynamics nor the control constraints can be treated separately.

An example of such is an enzyme which can have its conformation changed by an effector binding to its allosteric site, consequently changing its active site and affecting its catalytic capacity. Nonetheless, an enzyme can’t be completely described as a non-holonomic constraint, as it will lead to a poor description of its behaviour, a part of which can be better approached as thermodynamically driven and as a rate-dependent process, namely regarding its folding, change of conformation over time, and its overall stability [5].

If there seems to be a “tenuous” connection between rate-(in)dependent and (non)-holonomic constraints, it’s of the sort that Cariani writes about [5]:

A given physical system with complex interrelations between its parts can be described by various combinations of these integrable and nonintegrable constraints, but as more of the system is described via the rate-dependent processes, the explicit rate-independent relationships fall out of the description.

and

The nonholonomic constraints are the only means we have of altering the motion of the physical system. If we add enough nonholonomic constraints to the physical system, we can completely eliminate the rate-dependent motions, thereby allowing us to completely specify a trajectory of the system which is independent of rate.

It is under this notion that a computer is considered to be a maximally non-holonomically constrained system.

2. Biological organization as self-constraint

Organisms are said to be systems which can both construct and maintain themselves. They aren’t merely self-organizing, as they can also maintain the capacity to self-organize. And for such to happen, they must have some type of closure at the organizational level. They must maintain this capacity from within their organization [11, 13, 18-21, 23, 27-32, 6]. It is in this sense, that organisms are said to be self-determined, self-constrained, to be both the means and the end. This type of property is relative to the whole organism. The constraints in an organism are said to be mutually dependent. They hold a dialectical relation with respect to each other, and as such can’t exist independently. Through this view, we get to notions such as closure of constraints [27, 28], where each constraint in the organism’s organization needs to produce at least another one. Every critical constraint, that is, every constraint which is necessary for the maintenance of this capacity of the organism to manufacture itself and to maintain said self-manufacturing capacity, needs to be accounted from within its organization. It needs to be produced from within the system. This is how organisms achieve some type of causal closure, and how a minimal form of autonomy is achieved. It should be noted that this isn’t about physical closure, and it isn’t about a system becoming isolated from its environment. Much to the contrary, any system which is to achieve organizational closure must necessarily be at far-from-equilibrium conditions. It must continually do work in a constrained manner in order for closure to be maintained, and being thermodynamically open is a necessity. Furthermore, one shouldn’t associate closure to permanence, neither of constraints nor of relations between these. What needs to be achieved is continuity of this organization, regardless of what constraints might be present, which should be somewhat clear over the discussion.

Kant was perhaps one of the first to capture this notion generally [16], along with the notion of “self-organization” which now might merely stand for systems which come to be more organized, but which can’t maintain the constraints that allow such organization:

An organized being is then not a mere machine, for that has merely a motive power; but it possesses in itself formative power, and such a one, moreover, as it communicates to the materials, which do not possess it (it organizes them). Thus it requires no other purposive principle for its maintenance than the one which it itself produces. In such a product of nature, every part is thought as if it exists only by means of all the others, and so exists for the sake of the others and the whole, i.e., as an instrument (organ). And this reciprocal causation of the parts in the whole distinguishes a machine from an organized being. In the former, the parts only act on one another in turn (so that one part is the instrument of the motion of the other); but in the latter, the parts are reciprocally cause and effect of their form.

It’s through this organization, which is inherently circular and impredicative, that the concept of intrinsic teleology emerges [17, 22, 24-26], as Kant was preoccupied with [16, 17]. Of an organism being a system which is both means and end, being a goal-directed system under which goals are a product of intrinsically produced constraints, and for which the notion of normativity is completely adequate. Of a system for which some processes are good, and some are bad. Of a system for which some processes contribute to its autopoietic (as in self-producing) capability, while other ones serve against it. In all of this description, there’s a system which is an implicit beneficiary, and which is individuated. This in contrast with other approaches which take this goal-directedness for granted, and as a mere heuristic principle (i.e. teleonomy).

It’s important to note that the references given are in no manner exhaustive, nor is the way in which they are given suppose to give the impression that these approaches are “all in the same bag”, as they show crucial differences with respect to each other. Where they are similar, one can argue, is in emphasizing that what differentiates organisms from other physical systems is their organization. All of them could be said to put the organism in a pedestal, as an object (or process) which deserves to be studied as a thing of its own.

3. (Very) brief introduction to (M, R) and (F, A)-systems

An approach which captures organizational closure in a more formal manner is Rosen’s Metabolism-Repair (M, R)-systems [11], which has been extended by Louie [35-37], and has been mapped to a more biological context by Hofmeyr as Fabrication-Assembly (F, A)-systems [34]. These make the use of the four Aristotelian (be)causes, and so we need to cover them first very briefly. I’ll be making use of their definitions as they are put by Hofmeyr in [33] and [34], as he contextualizes these with respect to components and processes happening in cells. However, along the discussion I’ll try to argue for a different view of one of these (formal cause), as it necessarily relates to how Pattee describes informational constraints. This necessity comes from something that Hofmeyr writes about, close to the end of [34]:

[…] and the openness to formal cause ensures that it is informationally open.

But for now this spoiler will do. Let’s get to the four Aristotelian (be)causes. These are given as [33]:

-

Material cause - What is it made out of?

-

Efficient cause - What makes (what produces) it?

-

Formal cause - What makes (what is it to be) it?

Furthermore, Hofmeyr distinguishes intrinsic from extrinsic formal causes, but overall the way he regards formal cause is as follows [34]:

Formal cause, the fourth Aristotelian “because”, is the answer to the question “what is it to be something” in the sense of being the actualisation of some prior model (the formal cause) of that something, model being used here in the broadest sense: a prior existing representation such as a mental or concrete image, an idea, a propensity, design, blueprint, template, program, mould, pattern or even a prior exemplar of that something.

As said prior, we’ll discuss this definition of formal cause a bit more later on, as it necessarily relates to what a symbol (and its material symbol vehicle) is/should be, with more contextualization from what Pattee writes about. For now, we’ll stand on this, and apart from a few examples exemplifying how these causes relate to each other, we’ll only come back to formal causation (also with respect to intrinsic and extrinsic ones as Hofmeyr puts) when (briefly) introducing (F, A)-systems, as Rosen doesn’t use both formal and final causation in his (M, R)-systems (at least explicitly).

- Final cause - What is it made for (in terms of function or purpose)?

A few examples might do the work. A first one without much to do with biology might be, as Hofmeyr gives in [33], a table. The material cause for the table are the set of components needed to build it such as wood and screws, the efficient cause is the carpenter which builds it, the formal cause is the blueprint for such table (either in the carpenter’s head, or as physical blueprint which the carpenter every now and then checks to see if he’s building the table correctly), and let’s say the that carpenter also likes to write novels, then the final cause for the table would be to provide a surface over which he could write in a stable manner.

Now, a more biologically related example. A polypeptide would have as material cause the aminoacids, as efficient cause the ribosome, as formal cause the corresponding mRNA with sequence information, and the final cause could only be evaluated given an understanding of what role as “processor” or catalyst, such peptide might have in a cell. As we’ll see in a moment, in systems which have closure of constraints, the final cause of one constraint will often coincide with the efficient cause of another one. It’s important to note, that this example would be classified by Hofmeyr as one of freestanding, or extrinsic, formal cause [34], where formal and efficient causes are different entities. As opposed to intrinsic formal cause [33, 34], where the formal cause is an intrinsic property of the efficient cause (or even in some cases of the material cause). This is what I’ll argue about later, not making the most sense if seen through some contextualization with Pattee’s work. It can’t be overemphasized that these notions of formal cause are completely correct and adequate for Hofmeyr’s apparent purpose of extending (M, R)-systems and mapping this extension to cells as we currently understand them [33, 34], but that such notions could be better put in order to highlight how such systems got to an already reasonable level of complexity. Namely, trying to highlight how cells came to have informational (symbolic) constraints that form a completely arbitrary relation with respect to what they refer to. Hence, the link to Pattee.

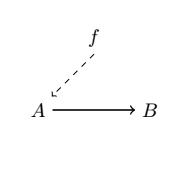

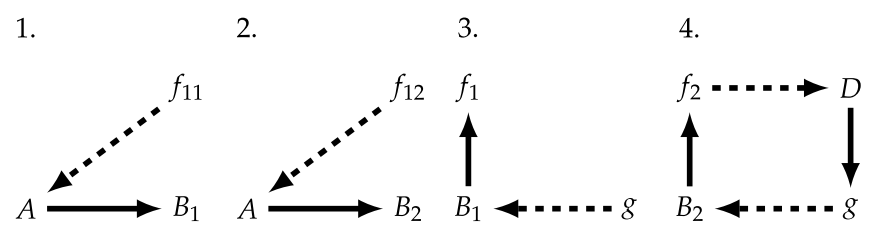

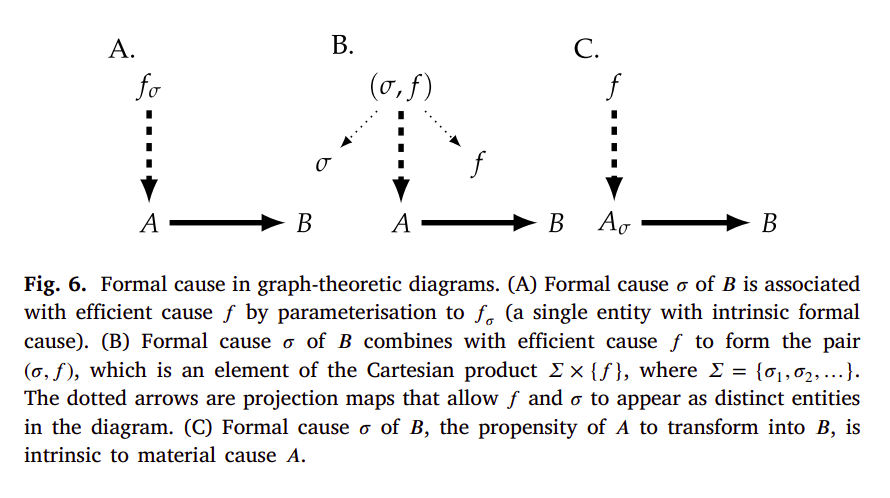

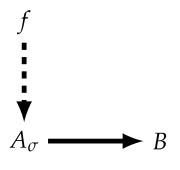

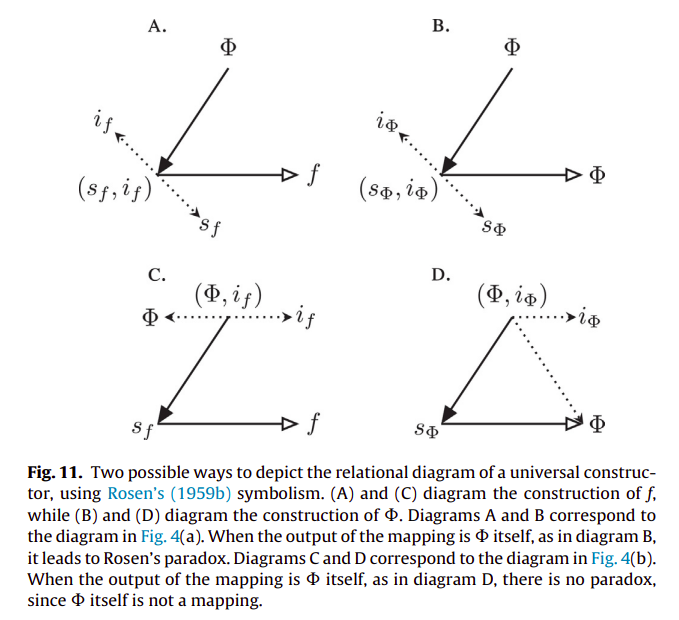

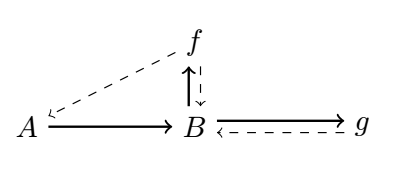

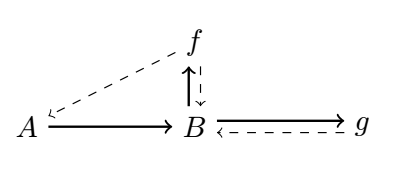

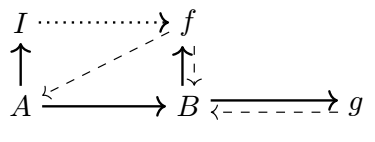

Let’s finally get to (M, R)-systems [11; see also 38-40 for relevant discussions]. If we consider a mapping $f: A → B$, then $A$ is considered to be the material cause of $B$, and $f$ is considered to be $B$’s efficient cause. This mapping can also be represented as a diagram in the following way:

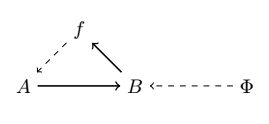

where material causation ($\rightarrow$) is represented by solid-arrows and efficient causation ($\dashrightarrow$) by dashed ones. Rosen refers to this mapping as “metabolic” and takes the interpretation of the processor $f$ being a specific mapping between the set of all of possible sets of substrates (or inputs) $A$, and the set of all sets of products (or outputs) $B$, such that $f(a) = b$ given $a ∈ A, b ∈ B$. We can also represent it as $f ∈ H(A, B)$, where the hom-set $H(A, B)$ is the set of all mappings from $A$ to $B$. However, he notices that $f$ is unentailed. There’s nothing producing the processor $f$. And so he adds another processor $\Phi$, which entails $f$. And so we get the following diagram:

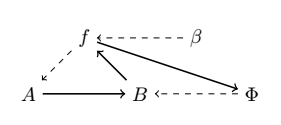

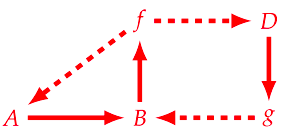

where the mapping $\Phi: B → H(A, B)$ is called “repair”, such that $\Phi(b) = f$ given $b ∈ B, f ∈ H(A, B)$. However, it has been argued that the notion of “repair” can be confusing, and so replacement is opted in its place [40]. As in, replacement of the corresponding processors or catalysts composing $f$. But now we are in a similar situation, $\Phi$ is not entailed, and so Rosen adds another processor $\beta$, and we have the following diagram:

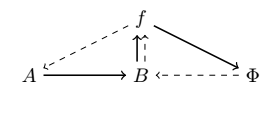

such that Rosen calls the mapping $\beta: H(A, B) → H(B, H(A, B))$ “replication”, with $\beta(f) = \Phi$. “Replication” here should be merely understood as replacing the replacement system [40]. However, the system is still not closed to efficient causation. $\beta$ is still not being produced from within the system. In order to stop the incoming infinite regress, of needing yet another processor to account for the previous one which was introduced, Rosen puts a very big restriction on what solutions are admissible to $\Phi(b) = f$. As it is said in [38]:

Rosen’s solution to avoid infinite regress, was to posit that the equation $\Phi(b) = f$ is to have only one solution $\Phi$ (a most demanding constraint indeed!) so that the mapping $\beta$ sends $f$ to this unique selector $\Phi$. In other words, $\beta$ is “just” the inverse of the “evaluation at $b$” operator (acting on functions whose domain contains $b$) so that no further procedure is needed to construct $\beta$ itself.

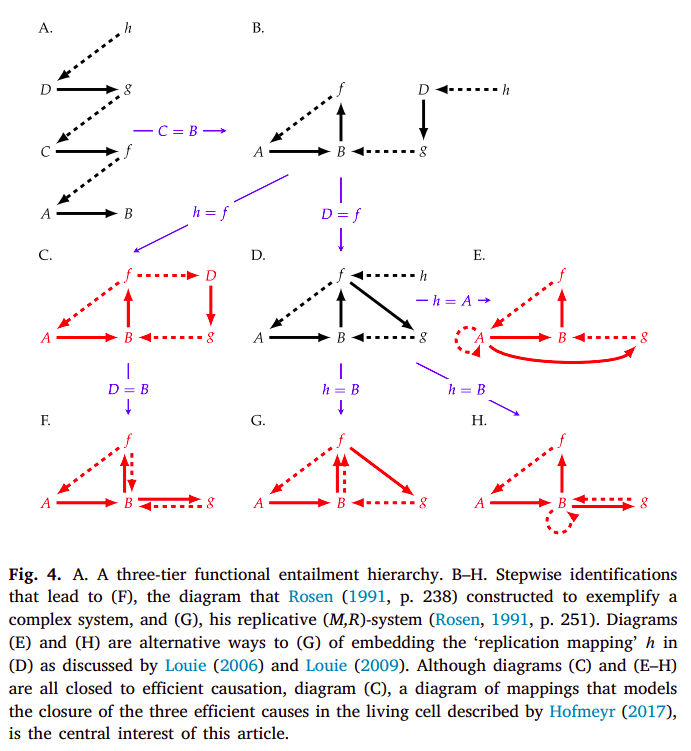

From this we obtain a diagram, which is now closed to efficient causation (and open to material causation; with an equivalence to closure of constraints and thermodynamic openness), with every efficient cause being produced by another one in the system:

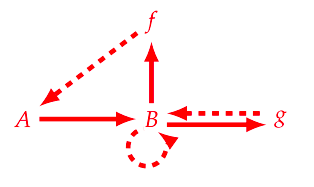

However, (M, R)-systems are only one type of example of systems which are closed to efficient causation. Hofmeyr gives some other ones [34]:

such that these (examples C, E, F, G and H) differ on how closure to efficient causation is achieved. The (F, A)-system in particular is as seen in diagram C:

still representing both the metabolism and repair mappings, the only differences being the absence of the replication mapping as Rosen had it implemented (diagram G), and having two unaccounted material causes in the system. As such, given that the (F, A)-system has both the metabolism and repair mappings, it can still be called a (M, R)-system, and is chosen particularly by Hofmeyr as the diagram which most reasonably represents our biochemical understanding of a cell [41].

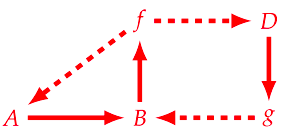

Now in the previous diagram, and in order to try to model it as a mechanism (important to note that this isn’t the “normal” definition of mechanism, but as defined in the context of Rosennean complexity [11]), $f$ serves under two mappings ($A → B$ and $D → g$), such that Hofmeyr splits it into the direct summands $f_{1} + f_{2}$. But by doing so, the same needs to be done for $B$, resulting in the following diagram [34]:

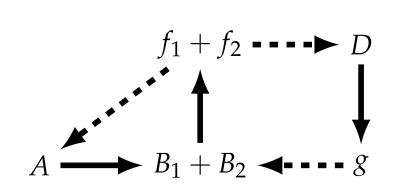

But in this diagram, for we to consider $g$ as being a monomorphic mapping (loosely associated to the notion of injectivity) such that $g: B_{1} → f_{1}$ and $g: B_{2} → f_{2}$, we now will need to split $f_{1}$ into $f_{11} + f_{12}$, with the corresponding sub-diagrams [34]:

And by doing this, we’ll again have to split $B_{1}$ into $B_{11} + B_{12}$. This results in an infinite regress, that Hofmeyr stops by making use of formal causation. That’s where we’ll go now. Additionally, it’s important to note that this splitting scheme is not unique and Hofmeyr describes other alternatives in [34], and needless to say has a much more indepth discussion of what was stated prior.

Hofmeyr’s first consideration of formal cause is associated to the need of making sense of the apparent paradox that Rosen found with respect to von Neumann’s universal constructor, as described in [33], and which I will come back to later, after visiting a few other related themes that might give a different view on what formal causation is/ought to be, as related to symbols and symbol manipulation (in the context of a code), as has been hinted a few times before. Crucially, many of these considerations will be about the emergence of said symbols, and of the arbitrary relations between these that we might characterize as a code. With that said, we’ll briefly consider a few examples of formal causation as exemplified by Hofmeyr in [34]:

Here, diagrams A and C represent intrinsic formal causes, and diagram B that of an extrinsic (or freestanding) formal cause. More specifically, diagram A represents that of an intrinsic formal cause that specifies or “informs” an efficient cause. Hofmeyr gives an example such as the substrate specificity that an enzyme has. As said in [34]:

[…] would be an enzyme that catalyses (efficient cause) the reaction in an active site on the enzyme, the chemical configuration of which determines which particular substrate (material cause) the enzyme binds and which reaction it catalyses. The active site can therefore be interpreted as not only the site of catalysis, but also a prior model (formal cause) that is actualised as the product of the reaction.

and has he develops in a footnote:

Here the simplifying assumption is that the reaction rate in the absence of enzyme is negligible, so that the reaction product for all intents and purposes does not form without enzyme present. […] Similarly, the formal cause is a combination of, on the one hand, the specificity of the enzyme, which ensures that the active site of the enzyme “chooses” to bind and convert to B only substrate A and not any of the other compounds in the mixture, and, on the other, the intrinsic propensity of A to transform chemically into B.

with a further example of such description in [33]:

In phosphatases, as in most enzymes, both catalytic and substrate specificity are determined by the same active site, but there are enzymes, such as proteases, in which catalytic and substrate specificity are determined by distinct sites on the enzyme. Even so, both efficient cause (catalytic action) and formal cause (substrate specificity) still remain associated with the same material entity (the enzyme protein).

This is one of the examples I will touch upon when (re)defining formal causation after some consideration from Pattee’s work.

As for diagram B, Hofmeyr gives as an example the production of a polypetide from aminoacyl-tRNAs (material cause) with mRNA as its formal cause, and the ribosome as its efficient cause. And regarding diagram C, a typical example is that of the intracellular milieu acting (efficient cause) on a yet unfolded polypeptide (material cause) with a specific sequence of aminoacids (formal cause), resulting in a folded protein (with or without - e.g. intrinsically disordered proteins - a specific set of conformations we can associate to the native state) [33, 34]. As Hofmeyr writes [34]:

In these examples the information for how to fold and to self-assemble is provided by the amino-acid sequence itself and by the chemical properties of the protein subunits: the formal cause is intrinsic to the material cause. However, correct folding and self-assembly can only take place in a specific chemical context, here a watery environment with buffered pH and strictly controlled ionic strength and electrolyte composition in which the molecules move around and collide through Brownian motion.

This is also an example of the use of formal cause I’ll touch upon. But formal cause was invoked for a reason, namely to stop the previously stated infinite regresses. Hofmeyr illustrates the use of formal causation as specifying a mapping, with regards to a general abstract model of a manufacturing system, which is constituted by fabrication and assembly processes (thus the name (F, A)-systems). This is heavily influenced by von Neumann’s self-reproducing automata [42], and so we should have a first very brief contact with it, and keep discussing Hofmeyr’s (F, A)-systems afterwards. We’ll return later to this for a second round.

3.1 A first look at von Neumann’s self-replicating automata

For some known as a Byzantine historian [48], von Neumann also took a great interest in many other things. One of those was over how organisms could not only maintain their complexity but also increase it, for which he developed an abstract model tackling self-replication [42, 63], based very much on the notion of Turing’s universal computing automaton [64]. The general automaton system which is capable of self-replication is described as being constituted by $A + \phi(X)$, where $A$ is a universal constructor which can build any machine $X$ from physical components in its environment according to the machine’s description $\phi(X)$. Such universal constructor can of course build a copy of itself according to its description $\phi(A)$ from available physical components, but it can’t build another description $\phi(X)$ in order for it to be incorporated into the newly built $A$, and to render this new automaton capable of self-replication. For such to be possible, von Neumann also adds a description copier $B$ and a controller component $C$, which can carry out the assembly of the new automaton with the introduction of $\phi(X)$ into $A$. As such, the general scheme of self-replication is: $A$ can carry out the construction of $A + B + C$ from the description $\phi(A + B + C)$, $B$ creates an additional copy of the description $\phi(A + B + C)$, which after assembly by controller $C$ results in $A + B + C + \phi(A + B + C)$ [42-44, 63, 33].

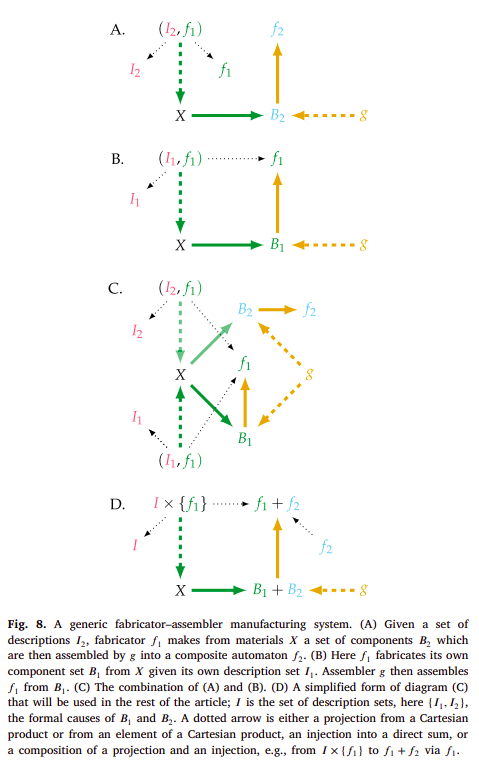

There are two general processes here under the guise of fabrication and assembly, which Hofmeyr jointly calls manufacture [34]. It is to these notions of fabrication and assembly, and to their corresponding representation that we’re going to turn again. More specifically, to how the previous notion of formal cause as description specifies for a certain mapping, essentially constraining the efficient (or material) causes, and stopping the infinite regresses that were stated prior. In the following diagrams, Hofmeyr represents these processes in a system which is yet to be closed to efficient causation and which can essentially be mapped to a 3D printer, like the RepRap, being able to print its own components (or atleast majority of them) [34]:

For instance, diagram B might exemplify a RepRap ($f_{1}$) that builds components parts $B_{1}$ from material blocks $X$ according to description $I_{1}$ of these parts, and which are then assembled by $g$ into a new RepRap ($f_{1}$). Diagram A exemplifies something a bit different, namely a RepRap ($f_{1}$) building component parts $B_{2}$ from material blocks $X$ according to their description $I_{2}$, and which are then assembled by $g$ into $f_{2}$, which can be interpreted to be anything other than the RepRap itself ($f_{1}$), perhaps a different non-functional one. This is because $f_{2}$ is not entailing anything in such diagram, rendering it non-functional. But it is clear that by using a set of descriptions from $I =${$I_{1}, I_{2}$}, a certain mapping can be specified, namely $(I_{2}, f_{1}): X → B_{2}$ or $(I_{1}, f_{1}): X → B_{1}$. But how should one interpret what $g$ is in this context? We might say that in the case of diagram B, it is someone which assembles the parts into a new RepRap. The 3D printer itself can’t do it.

But now we have another problem. What about $g$? Don’t we need to do the same specification for the $g$ mapping? Shouldn’t we also have some type of description for how to assemble the parts? For the case of the person assembling these parts it would of course be a description, or a representation of the process of assemblage of these parts in their head, or in a physical blueprint exemplifying such assembly. However this necessarily obfuscates the problem (what is a representation, description, what symbols have to do with it, and what are symbols) and which Pattee might have something to say about. So let’s not think about how a person might do such assemblage, nor think too much about what we mean by description now. Let’s assert that the RepRap itself might come to have some type of assembly system. How would such specific parts be assembled in a specific manner (as a concrete mapping)? As Hofmeyr puts [34], this is very difficult to imagine for a RepRap at the macro-scale, but is much more reasonable to think about at a molecular scale. Namely, such specification for assembly will come in a similar form to the type of formal cause which is intrinsic to the material one, that was introduced before:

As Hofmeyr says [34]:

Such a context would be difficult, but not impossible, to imagine for the macro-scale at which RepRap operates, but is eminently feasible at the nanoscale where molecules move, collide and react freely through Brownian motion.

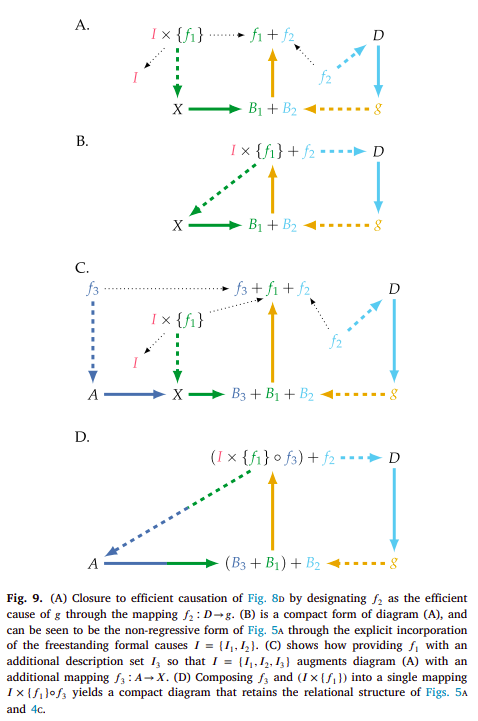

Following this, Hofmeyr adds another material cause ($D$) which is mapped to the mapping $g$ by $f_{2}$, in order to close the system with respect to efficient causation (diagrams A and B). Finally, he provides an example of how by adding another description set $I_{3}$ specifying $f_{1}$, the diagram is extended by having the mapping $(I_{3}, f_{1}): X → B_{3}$, which allows $g$ to map $B_{3}$ to a new mapping $f_{3}: A → X$ (diagrams C and D) [34]:

Hofmeyr then proceeds to talk about understanding (and contextualizing) the cell with respect to these relational diagrams, discussion which I won’t refer to here. So I highly advise checking [34, 41, 33] not only for this, but also for a better discussion of what was previously stated, as this one is a very brief and shallow introduction which isn’t at all supposed to be self-contained.

We’ll come back again to the topic of von Neumann’s self-replicating automata, but for now let’s visit some other pastures.

4. A (very) brief detour into Deacon’s autogen

An approach which captures a bit of the essence of a system composed by coupled self-organizing processes which compensate for each other’s dissipative tendencies is Terrence Deacon’s autogen [30, 31, 24, 25]. As I hope it will be clear over this short detour, this type of system shows normative properties, of something being either good or bad for such system. I hope to transmit enough, such that what García-Valdecasas and Deacon say in [24] is obvious and trivial:

As a result, the normativity of life is not superimposed by external observation. It is an either-or relationship between potential causal alternatives of what is constantly at risk of dissolution that grounds value talk. Our normative categories are hence not projections.

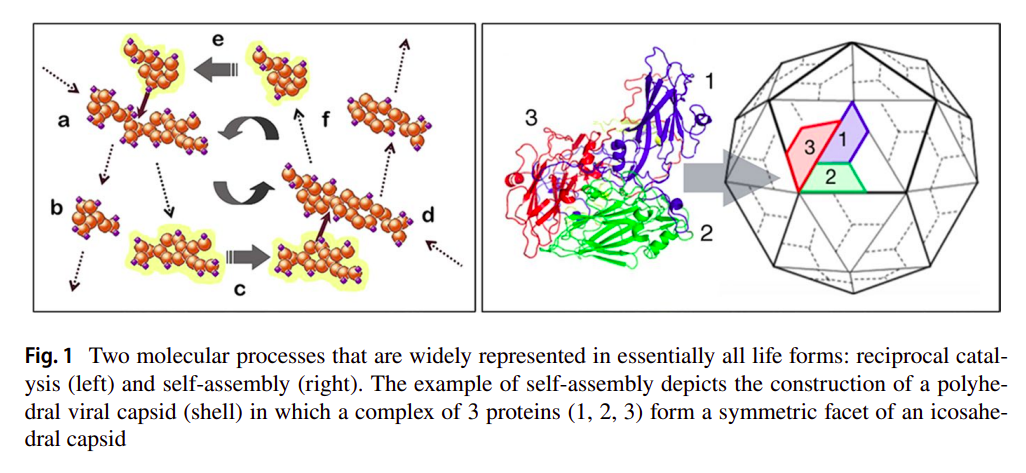

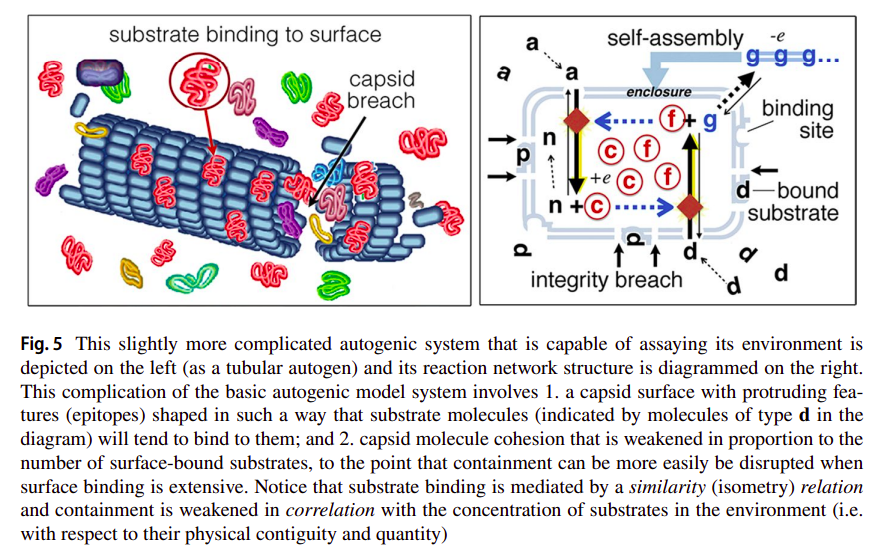

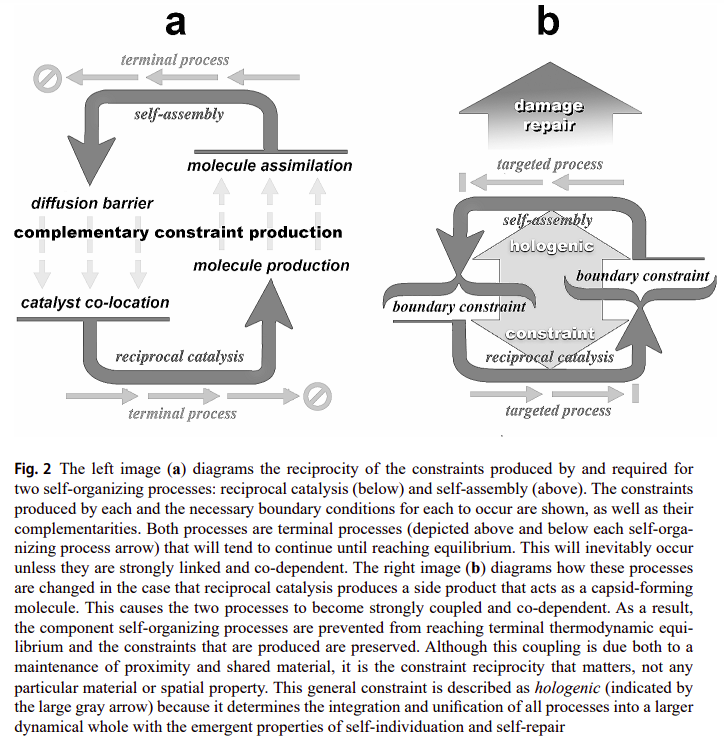

The autogen is a simple hypothetical model showing two self-organizing processes producing each other’s critical boundary conditions. The first one is reciprocal catalysis where each catalyst necessarily catalyzes a reaction which produces another one of the needed catalysts, in order to achieve closure (such that the network is deemed autocatalytic [46]). More importantly, said catalyzed reactions should also produce by-products which will serve under the second process, this one being self-assembly. Deacon proposes that some of the by-products could be similar to protomers which will self-assemble to form a capsid-like structure, much like what happens with viral capsid assembly [45], and as seen in the following figure [31]:

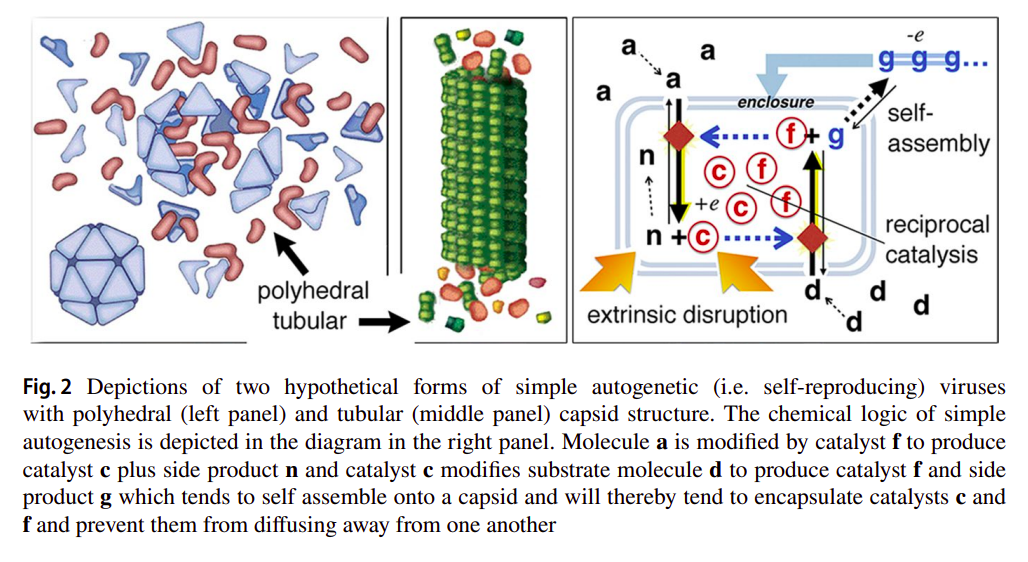

The autogen (short for autogenic virus, which Deacon states as a non-parasitic virus which can produce its parts) is then constituted by two complementary self-organizing processes that produce the conditions for the other to occur, as stated in [31]:

So reciprocal catalysis produces high locally asymmetric concentrations of a small number of molecular species while self-assembly requires persistently high local concentrations of a single species of component molecules. Likewise, self-assembly produces constraint on molecular diffusion while reciprocal catalysis requires limited difusion of interdependent catalysts in order to occur. In this way reciprocal catalysis and self-assembly are molecular processes that each produce the boundary conditions that are critical for supporting each other.

and

These process can become coupled and their reciprocal relationships linked if one of the molecular side products generated in a reciprocal catalytic process tends to self-assemble into a closed structure. In this case capsid formation will tend to occur most effectively where reciprocal catalysis occurs. But this increases the probability that capsids will tend to grow to enclose a sample of the reciprocal catalysts that both produce one another and capsid-forming molecules. As a result, catalysts that reciprocally depend on one another to be produced will tend to be co-localized, and prevented from diffusing away from one another.

as exemplified in the following figure, with two variants of the autogen with different capsid geometries [31]:

Furthermore, Deacon already hints at some capabilities that the autogen might have with respect to repairing and reproducing itself [31]:

While contained, catalysis will quickly cease when substrates are used up, but in the case that the capsid is subsequently damaged and spills its contents, more catalysts and capsid molecules will be synthesized if there are additional substrate molecules nearby. So damage that causes an otherwise inert capsid to spill its catalytic contents into an environment with available substrates will initiate a process that effectively repairs the damage and reconstitutes its inert form. Moreover, depending on the extent of the damage, the distribution of catalytic contents, and the concentrations of substrate molecules the process could potentially produce a second copy of the original from the excess catalyst and capsid molecules that are generated.

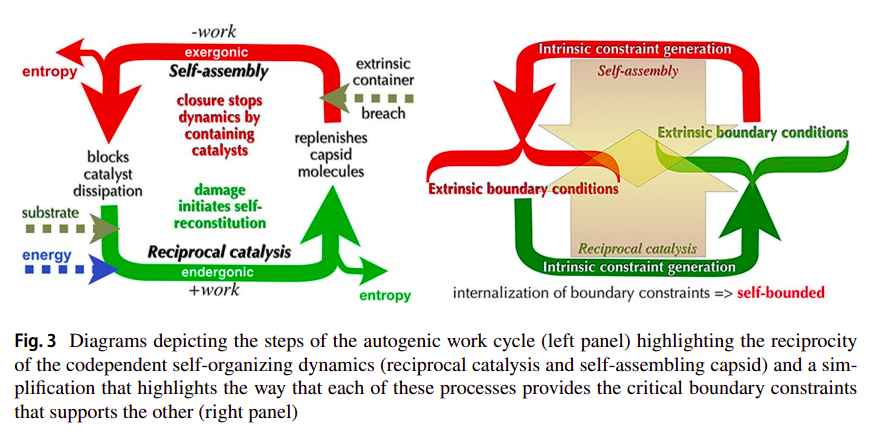

Deacon calls this coupling between the endergonic (reciprocal catalysis) and exergonic (self-assembly) processes, but which in this context has the endergonic being further constrained by the exergonic one, an autogenic work cycle as a reference to thermodynamic cycles, and further with respect to Work-Constraint (W-C) cycles [29], as illustrated in the following figure [31]:

As Deacon states [31]:

This produces a higher order work cycle in which the entire molecular system cycles from disrupted to reconstructed, dynamic to inert, and open to closed. When returned to the reconstructed inert phase the system has been returned to an initial state from which the cycle can again be repeated. At this point the work of self-reconstruction has produced a far-from-equilibrium structure with a relatively high threshold required to dissipate it (in the form of capsid damage). And yet when loss of integrity due to extrinsic damage is sufficient to initiate change toward equilibrium the re-initiation of catalysis and self-assembly works against this.

This is what makes both processes co-dependent and the relation between them dialectical. If one doesn’t exist, the other dissipates away. These aspects have some overlaps with what was referred to before regarding organizational closure and closure of constraints, and such concepts being different from physical closure, as Deacon says [31]:

An autogen is therefore self-individuated by this intrinsic co-dependent dynamical disposition, irrespective of whether it is enclosed or partially dispersed.

Furthermore, such autogen given the cycling between open and closed structures will have some molecules diffuse in and out of itself, and thus both a minimal form of variability and correspondent evolvability can be achieved [31]:

Captured molecules that incidentally share catalytic inter-reactivity with autogen catalysts or capsid molecules will tend to be incorporated and replicated. This will create variant autogen lineages. Those captured molecules that don’t interact with autogen-intrinsic molecules or impede the process without being lethal will tend to get crowded out and eventually passively expelled into the environment in successive reproductions because they are not replicated. This provides a capacity to correct error and to evolve.

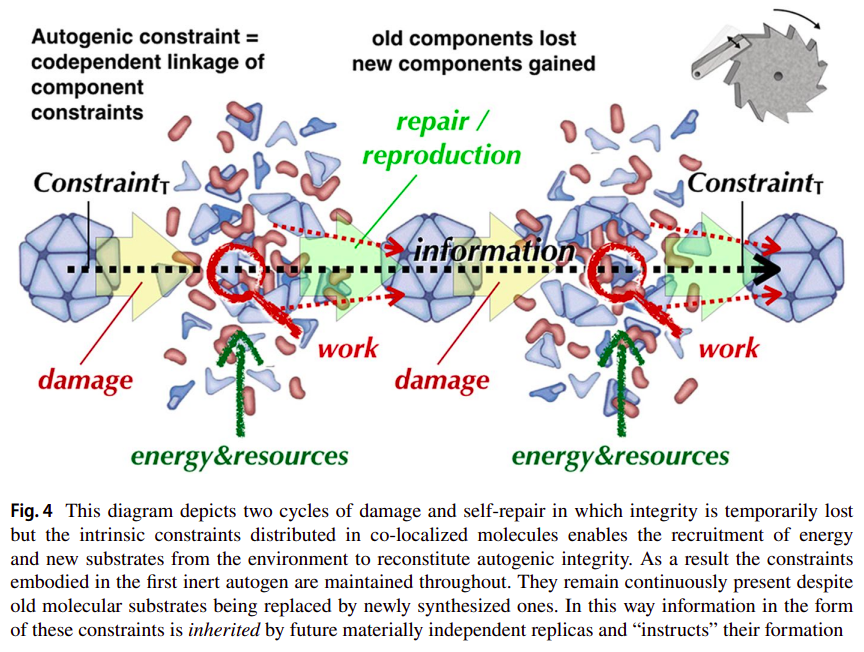

Deacon further describes how this circular relation exemplifies how inheritance of constraints is achieved through multiple autogenic work cycles, even if of a very limited form, which won’t allow much variablity without the system ceasing to be. As is seen in the following figure [31]:

This has much to do with the notion of some constraints being a record or description for the “instruction” of the system’s lower level dynamics (and corresponding rate-dependent constraints). Such description shouldn’t be as complex as the dynamics it constrains (it shouldn’t be affected by the dynamics it is constraining), as we’ll see later, if the system is deemed to be evolvable in an open-ended manner. Additionally, such description will often be associated to rate-independent constraints (given their possible information carrying capacity), and to what in some cases we’ll be able to classify as symbols (or as their vehicles).

It’s important to note that Deacon makes use of semiotic terminology as in Peircean semiotics (namely, sign vehicles of all types (iconic, indexical, symbolic), interpretants and objects), throughout the discussion of the autogen [31], and that there isn’t necessarily a perfect overlap between how some of these terms are used by him, and by how Pattee uses them, and if Pattee even uses all of them at all. As Pattee states in [47], most of these differences stem from the following:

At this molecular genetics level Peirce’s elaborate sign vocabulary, especially interpretation, is gratuitous. The triadic concept of interpretation makes sense only at higher levels where there is the possibility of choosing alternatives. We usually accept the concept of choice at the cognitive level, although the ontological status of choice is still an unresolved classical philosophical problem. Biosemiotics needs to define objective criteria for invoking interpretation at every evolutionary level.

Nonetheless one should be aware that the reference that Deacon and Pattee make to signs is always within the context of a system which is deemed autonomous and which can make use of such sign vehicle, as seen in the following examples, respectively [31] [43]:

Any property of a physical medium can serve as a sign vehicle of any type (icon, index, or symbol) referring to any object of reference for whatever function or purpose because these properties are generated by and entirely dependent upon the form of the particular interpretive process that it is incorporated into. […] Thus, we should not ask what it is about some sign vehicle that makes it an icon index, or symbol. These are not sign vehicle intrinsic properties. Intrinsic properties are not what make something semiotic. Sign vehicle properties aren’t irrelevant, of course. But intrinsic properties are merely semiotic affordances (to borrow a concept from ecological psychology). They may or may not be utilized for any semiotic purpose.

and

Examples of direct shape-matching processes are the copying of the base sequence in nucleic acids and the binding of a substrate by an enzyme. I should emphasize here that the physical interaction of base pairing and substrate binding are not in themselves functional or semiotic processes. It is only by virtue of their roles in the process of self-replication that they are interpreted as functional. Such a template might be interpreted in Peirce’s terms as an iconic sign.

Getting back to the autogen, Deacon wonders further: what if the capsid structure is sensitive to the same substrate molecules which are used by the catalysts, in its environment? Perhaps the capsid integrity can be decreased proportionally by the amount of substrate molecules bound to it? Not only will the capsid collapse under conditions which are favourable for replication, but this same fragility will be scrutinized under selection [31]:

This will make containment more likely to fail and release catalysts in reproductively supportive conditions. Moreover, the threshold level at which capsid integrity becomes unstable is a variable that is subject to a form of natural selection. So, over time, autogenic lineages more likely to break open when the concentration of external substrates is optimal for successful reconstruction and reproduction will tend to replace those whose sensitivity is less well correlated with successful self-reconstitution.

Such variant of the autogen is illustrated in the following figure [31]:

Now Deacon makes another change to the autogen. With some hints from Dyson [49], where nucleotides are first considered to take an energetic role, and only later additionally acquire an informational one, Deacon considers a version of reciprocal catalysis that also generates as a by-product molecules like tri and di-phosphated nucleotides such as ATP, GTP, ADP, UDP, etc (or corresponding deoxy-versions dATP, dGTP, etc), whose hydrolysis into either di or mono-phosphated form could be coupled to other endergonic processes that might otherwise not happen in the autogenic versions considered before. However, Deacon recognizes that in a scenario where the autogen is fully closed, in its inert phase, the corresponding hydrolysis of these tri and di-phosphated nucleotides might potentially be disrupting to the capsid structure [31]. A viable option is the polymerization of these into nucleotide polymers by a condensation reaction, essentially providing a stable form that can later be used given depolymerization (examples of such polymers are RNA and DNA, although presumably these would only be present under their single-stranded forms; double-stranded forms would probably only appear given base-pair complementarity between different single-stranded polymers, or given some type of cleavage of the same single-stranded polymer which happened to fold in a particular manner forming a more intrincate secondary structure). Evolutionarily, autogens that don’t have some catalysts with some polymerization capacity, and specially in scenarios where there isn’t enough substrate in the environment to further compensate the damage created by such exergonic process, won’t be selected for. Of course the converse can also be taken into account, i.e. in scenarios where there’s an abundance of substrate, having this type of internal disruption might actually be beneficial. As it might be perceptible, one of the main aspects that the autogen lacks is an internally mediated mechanism for disruption of the capsid, in order for it not to be completely dependent on external disruptions. This has been noted by some, namely [50, 51].

Ok, what about the informational role? The following is what Deacon will refer to as offloading of constraints [31]:

The capacity to transfer constraints from one physical medium to another quite different one makes possible the transfer of the holistically embodied dynamical constraints of autogenesis onto a different sort of material substrate such as a nucleotide polymer.

And this will be done for a specific reason, namely to overcome a molecular combinatorial catastrophe, this one being described as [31]:

A molecular combinatorial catastrophe can arise for autogenesis when the number of interdependent molecular interactions required to produce successful autogenic repair or reproduction increases. As the number of molecular species that need to interact increases linearly, the number of possible cross-reactions that could occur between members of the set increases geometrically. This is a problem because only a small fraction of these interactions will be supportive of autogenesis. The proliferation of alternative interaction possibilities will therefore compete with supportive interactions—using up critical components and wasting free energy. This will decrease efficiency and impede reproduction. So autogenic systems like the ones described above have limited evolvability, making autogenic evolution improbable beyond very simple forms. So unless non-supportive reactions can be selectively suppressed, autogenesis cannot lead to more complex forms of life.

Following this, Deacon generalizes what is seen in the context of the enormous complexity present in the cell’s genetic regulation as entailing constraints. Constraints of which reactions should happen and which shouldn’t, regardless of these being very complex constraints:

So, although we generally tend to conceive of DNA-based synthesis of proteins as a generative process, it can also be considered to be the principle constraining influence that keeps deleterious reactions at bay.

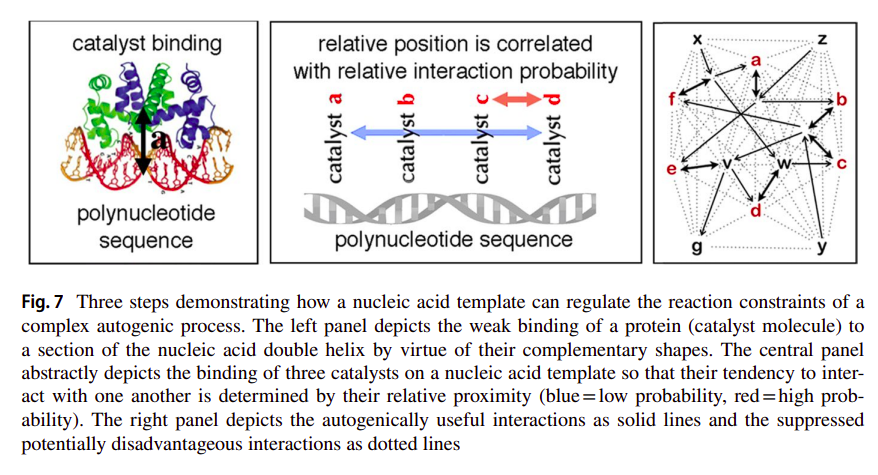

As we’ll see later (and as we have already seen a bit before), these types of constraints should be rather stable and more or less energy-degenerate (equiprobable) structures. And this is of course what these nucleotide polymers are. Regarding polymerization, for the major part there are very little biases towards which nucleotides are going to get introduced into a polymer, given that the corresponding nucleotide base only minimally contributes to the stability of the phosphodiester bond formed between the (deoxy)ribose and phosphate groups of the corresponding nucleotides. What results, is more or less, the formation of polymers with random sequences. But of course, even if the sequence of such polymers is arbitrary, they will still have different conformations (even if reasonably linear in general) which are sequence specific. As such, they can serve as templates to which other molecules can bind, namely those catalysts that were constituting the autocatalytic network. As Deacon states [31]:

These structural differences will determine corresponding differences in how other molecules will tend to attach to the polymer due to their shape and charge complementarities. Since there will be both catalysts and polynucleotides within the inert autogen capsid, free catalysts will tend to associate with free nucleotide polymers with respect to these structural complementarities. The attached catalysts will therefore tend to be arranged into distinct sequences along the length of an extended nucleotide. The spatial correlation relationships between catalysts aligned along a nucleic acid polymer will thereby tend to constrain the probability of particular catalytic interactions, increasing some and suppressing others. In this way the structural constraints of the template molecule can bias and constrain the interaction probabilities of the catalysts.

which is captured in the following figure [31]:

On this basis, nucleotide polymers that optimally represent the interaction network by constraining catalyst proximity (as in providing the optimal repair and reproduction rates), will tend to get selected. What were once only dynamical rate-dependent constraints, have now been offloaded onto a reasonably stable and somewhat rate-independent constraint. What were once catalysts which needed to have some specific properties to allow proper co-localization with respect to other catalysts, can now be replaced by ones which have a better catalytic capacity for example, regardless of their interaction specificity. What a rate-independent constraint allows is the control of a dynamics it is minimally affected by. Likewise, any modification of such template will effectively result in a different interaction network. Any variability that comes in the form of other molecules from the environment will be much less disruptive to the autogen than before. As Deacon states [31]:

The template is also subject to quite different chemical and physical influences than is the rest of the system. But the informational codependence between template and dynamics means that template modifications will have consequences for the dynamical organization of the whole system. Thus continuity of constraint across the change in molecular substrate can bring otherwise dynamically unrelated and independent physical–chemical properties into interaction with one another in ways that exploit their possible synergies.

It is through this view, that we start to get a notion of a code, of a set of arbitrary relations between two domains. But why are such relations arbitrary? Arbitrary here means that they don’t emerge out of physical necessity. They emerge, evolve, and are preserved based on what relations allow the autogen to maintain its autonomy. Here, these two domains are the nucleotides in the template, and the catalysts which weakly bind to them (or at least some parts of the catalysts which allow such binding). However, this is a bit different than what we associate to the genetic code, and a degenerate one at that. Of there being a concrete mapping we can perceive between a codon and a corresponding aminoacid being represented by such codon, and with an enormous amount of complexity supporting the conservation or change of such mapping if necessary, that can generally be captured by the central dogma of molecular biology and all of its “exceptions” which confer to these constraints some type of meta-linguistic capacity. This is a much cruder version of a code-like set of relations. As Deacon says [31]:

Although the genetic translation process is far more complex than the template-assisted autogenesis described here, there is an underlying abstract similarity in the way that the code-like (“arbitrary”) mapping in both is dependent on a particular combination of isometry and correlational relationships. In living cells distinct tRNA molecules become aligned with respect to mRNA template structure by virtue of codon-anticodon matching; i.e. isomorphism. And the correlation between a specific tRNA anticodon and the amino acid that is attached to that tRNA molecule enables correlational relationships between adjacent mRNA sequences to constrain corresponding correlational relationships between the amino acids constituting a protein. Analogously, the physical linkage between template and catalyst in template assisted autogenesis is also due to isomorphic similarity. This determines that structural correlations of template structure are additionally correlated with catalyst interaction constraints.

Such cruder version of a code-like set of relations is merely about a reasonable representation of what were once the dynamical interactions of the catalysts, by the template structure, these ones being constrained by catalyst proximity [31]:

The substrate transferability of constraints thereby fractionates the previously holistic system of dynamical constraints, displacing some onto a comparatively inert substrate. As a result the structure of the molecular template literally re-presents the topology of the dynamical network of interactions that functions to represent and re-produce itself. The result is what might be described as recursive self-representation; i.e. self-representation of self-representation. The circularity implied by this description refers to the way a part of a system is able to re-present the critical constraints of the whole system of which it is a part. […] Offloading interaction constraints onto a static structure enables that structure to reliably re-present and preserve those critical constraints irrespective of any potentially degrading efects of dynamical interactions. This is because the correlated structural and dynamical constraints are embodied in otherwise unrelated physical properties linked only due to the functioning of the whole.

Afterwards, Deacon develops a bit on a general scheme of (biosemiotic) scaffolding as introduced by Jesper Hoffmeyer [52] to talk about the complexity seen regarding the genetic code, most of which follows from this general statement [31]:

Thus diplaced affordance (in which the information-bearing medium is segregated from the constrained dynamical medium) is made possible by the way that coupled isomorphic (similarity) and correlative (contiguous) affordances can mediate the displacement of constraints from one physical substrate to another.

Nonetheless, I think most of what was “needed” from Deacon’s hypothetical toy model has been talked about, even if in a very shallow manner and without a proper discussion with regard to Peircean semiotics, which Deacon does make heavy use of. Additionally to [31, 30], some other references which talk about the autogen are for example: [53] regarding Deacon’s response to criticisms to [31] (for instance regarding the autogen’s lack of internal pertubations; if the use of Peircean vocabulary is reasonable; if the nucleotide polymers themselves would serve as good sign vehicles, in terms of providing good information carrying capacity, ssRNA for instance typically would induce some biases on which nucleotides would be further polymerized as it can fold into branch-like structures, loops and other secondary structures; etc); [24] on biological (intrinsic) teleology also emphasizing the multiple realizability of the autogen’s constraints, these being effectively underdetermined; and [25] also on biological teleology, and on some differences between teleodynamics as developed in [30] and other organizational approaches such as closure of constraints, autopoiesis, etc.

Let’s go now into some other things.

5. What are symbols and what are they for?

It should be noted that what is referred to here is mostly coming from Pattee’s and related work, and as such it can’t be generalized to biosemiotics as a whole. In fact, if Pattee’s work is to be adjacent to biosemiotics as a field, then it would probably be under the label of physical biosemiotics [7, 8]. Regardless, one thing is common between these: all and only organisms use symbols. Because a symbol (with its material vehicle) and what it refers to, is a relation that can only be made sense out of with respect to a system which is a self. Which is a potential beneficiary of this relation as an affordance, as we have already seen a bit of when talking about the autogen. Eventhough the material vehicles follow physical law, the corresponding relations between these and what they stand for, seem to be underdetermined by such “inexorable” laws. Furthermore, it starts becoming a bit clear that something isn’t inherently a symbol. And more than that, that there are probably going to be certain physical interactions which are only about symbol manipulation without reference to what these symbols stand for (syntactics), and others which do invoke what these symbols stand for (semantics). It is also in a similar sense, that notions of computation, as mere symbol manipulation, must be distinguised from other physical interactions which necessarily make use of the relation between symbols and what they stand for, i.e. measurement and control [5]. But first, what is a symbol? And when do these first emerge? Taking into account these questions, I will be mostly addressing scenarios like those of Deacon’s autogen as a toy model, unicellular organisms, etc, which could be considered to be minimal systems under which the notion of symbols, and the corresponding activity of using them ((bio)semiosis), emerges. Nonetheless, there are probably going to be certain situations under which I’ll make some reference to how symbols are “normally” understood in a more cognitively-biased context, as in regarding languages, formal systems, etc.

Some of the same intentions can be captured by Pattee’s work. Namely, in trying to understand how (and where) do symbols first emerge. Admittedly, Pattee’s consideration of this comes from various angles, but all essentially stemming from the same difficulty which has been a plague for centuries to millennia: how to make sense of a system which observes and a system which is observed, how to make sense of a system which knows and a system which is known, a system which controls and a system which is controlled, a subject and an object, and how to make sense of what seems to be the irreducible relation between these. This, Pattee calls the epistemic cut. And the correspondent minimal form of this, where this cut first emerged: the primeval epistemic cut [4, 54]. Most of the reference that I’ll make to Pattee’s work is regarding this primeval epistemic cut, of a minimal system which is able to self-individuate and separate itself from the environment. Again, here this “separation” is not meant in terms of physical closure, or thermodynamic isolation, but rather with respect to organizational closure as we’ve seen a bit of before. Through this, a system can be a concrete beneficiary, with the capacity to (re)manufacture itself in a more sofisticated manner that also allows for the maintenance of this capability. To be an organism, as it’s intuitively understood. In so doing, I’ll be mostly referring to the genotype-phenotype problem, such that other necessary similar epistemological distinctions, which fall under symbol-matter complementarities (e.g. mind/body), won’t be talked about much, as it’s impossible for one to not get completely disillusioned when considering their complexity. Pattee over his work [see 54 for a reasonable chunk of it] also considers and talks about other forms of such complementarities, such as: the necessary separation between laws and initial conditions, and the corresponding different descriptions of a measurement and the measuring device used for it (if one isn’t to get an infinite regress by needing to measure the state of the measuring device itself). Likewise, any mention of measurement will be made much closer to it as biosemiotician concept, than to it as in a conventional physics use.

With that out of the way…

Pattee in a similar manner to the organizational approaches referred before, assumes that organisms follow the same physical laws as every other system, and that what differentiates them is that organisms properly “harness” these laws, resembling what was said by Polanyi in [57]. Essentially, it’s a problem about organization of the corresponding constraints of a system. But there are different types of constraints, as we’ve loosely seen before, and more than that, there are different types of relations between these constraints. So what Pattee generally associates to organisms (or at least to ones which are evolvable in an open-ended manner) are systems constituted by symbolic control over matter. Ok! What are symbols!?

A symbol is very generally associated to something that stands for something else other than itself. And as we’ve already stated a reasonable amount of times before, a symbol doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Even if there are structures, which we’ll talk about in a bit, that make for good symbol vehicles, they aren’t inherently such. A symbol only makes sense in the context of an organism or another system which serves as the organism’s extension. As Pattee states in a footnote [4]:

I define a symbol in terms of its structure and function. First, a symbol can only exist in the context of a living organism or its artifacts. Life originated with symbolic memory, and symbols originated with life. I find it gratuitous to use the concept of symbol, even metaphorically, in physical systems where no function exists. Symbols do not exist in isolation but are part of a semiotic or linguistic system.

and in [58]:

Symbols are difficult to define in any simple way because symbols are functional, and function cannot be ascribed to local structures in isolation. The concept of symbol, like the more general concept of function, has no intrinsic meaning outside the context of an entire symbol system as well as the material organization that constructs (writes) and interprets (reads) the symbol for a specific function such as classification, control, construction, communication, decision-making, and model-building. […] The symbol vehicle is only a small material structure in a large self-referent organization, but the symbol function is the essential part of the organization’s survival and evolution.

What Pattee associates to these small material structures which can potentially serve as symbol vehicles are: rather inert and stable, energy-degenerate (equiprobable), rate-independent constraints, which by having these characteristics can have a high information capacity and serve as a stable memory structure in these systems [54]. A prime example of this, which has already been referred to before, are nucleotide polymers, which come to form rather random sequences, given that each base in the respective monomer barely contributes to the stability of the phosphodiester bond that is formed. So in this sense, symbols can be seen as attractor basins, or as “islands of stability” as Cariani puts [5]:

First and foremost, symbols represent the means of stabilizing relations between parts of an ever-changing system. Symbols can be seen as the more stable parts of the system which have the capacity to retain their identity despite constant change in the rest of the system.

It is also related to this matter that Pattee stresses some concerns over analog memory/codes being able to provide enough stability, in order to exist a separation between dynamics which are controlled by structures that are minimally affected by them [9]:

Important to note this: One can also define analog memory and codes as in analog computation. Analogs need not involve discrete symbols. This has been suggested by Hoffmeyer and Emmeche (1991), Juarrero (1998), Hoffmeyer (1998) and Barbieri (2003) in contrast to discrete or digital memories and codes. The problem with analogs is that they are all special purpose structures like individual molecular messengers that have limited informational capacity and that have no common code or interpreting process, as do genetic sequences. An autocatalytic or metabolic network may be interpreted as containing an implicit informational dynamics, but lacking an explicit passive memory structure and code it is difficult to imagine any open-ended evolvability. On the other hand, as Hoffmeyer (2000) suggests, some form of implicit analog codes may have existed as precursors of the explicit discrete codes of present life with regards to making a difference between what might be constitute a symbol or not (and corresponding code)

But where’s this necessity of a separation coming from? Of a separation between a dynamics and something else which controls such dynamics, but being rather inert with respect to it? It is to a somewhat informal argument made by von Neumann, that we’ll turn to in a bit, as he presumably was one of the first to make this connection. But we can already see a very clear similarity between this, and what was stated in the context of Deacon’s autogen, regarding a molecular combinatorial catastrophe and how to prevent it. Furthermore, some of this also relates to what was mentioned with respect to (F, A)-systems (and the use of formal causation), which we’ll revisit in a moment.

Coming back a bit to what was being discussed, Pattee when discussing the notion of symbols with regards to a minimal system, almost always gives the example of a cell with corresponding processes that can be captured by the central dogma of molecular biology (and its “exceptions”). The problem here is that there’s an enormous gulf between the complexity in said cells, and for example in a toy model like Deacon’s autogen that shows a very “dubious” conception of a code-like set of relations (we can perhaps state that the mapping would be between corresponding nucleotides and some small part of the catalysts which would serve similarly as a binding domain). When we think about a code, we inherently think about the mapping between the codons (in DNA and mRNA) and the respective aminoacids (given the matching between codons-anticodons in tRNA). Almost always when discussing symbols, and a symbol system, Pattee pre-assumes an already formed code. Where does this code come from (nevermind the fact that Deacon doesn’t necessarily give a solution to this)? And where do all of the regulation layers associated to transcription and translation processes, and beyond, that confer to these constraints a type of meta-linguistic capacity come from (to a system which has such meta-linguistic and self-referential capacity, Pattee says it has semiotic closure [58], term of which was better introduced by Luis Rocha [44]; essentially such system has the constraints which write onto and read from the symbolic constraints, also being described by those same symbolic constraints; for instance a cell is semiotically closed)?

I think Deacon’s autogen already gives a more generalized notion of how symbol-grounding might be achieved, as given in the following context [59]:

I want to emphasize that what a symbol stands for cannot end with just another symbol. The referent of a symbol is an action or constraint that actually functions in the dynamical, real-time sense.

If we think about symbol-grounding in this much more general manner, and not necessarily through the example that Pattee often gives [60]:

The origin of the genetic code and genetic language is still the greatest mystery, but whatever the answer, it is a fact that for over 4 billion years of evolution linear copolymer folding has remained the essential symbol grounding process that enables 1-dimensional genetic symbolic descriptions to construct and control the 3-dimensional molecular machinery of all life. These folded molecules also remain as the initial detectors of sensory information at all levels of evolution.

then Deacon’s autogen (as provided by template-assisted autogenesis) seems to already conform to this. We can perhaps think of an example where some molecules in the environment of the autogen bind to some capsid molecules, leading to some conformation change of these, causing a much less specific type of signaling cascade (through whatever free catalysts are available), which might eventually lead to (de)polymerization of the corresponding template nucleotide polymer, resulting in a slightly different interaction network. Of course this is very far-fetched. However, the point is to provide an idea of how symbolic constraints might be used in systems where specificity is very low. Otherwise, it’s very hard (being charitable) to think about how the enormous complexity, through all the hierarchical constraints [61], in cells even emerged. And more than this, to understand if what we generally call the central dogma of molecular biology (with the exceptions) is the general or a specific case, which allows such separability between rate-dependent constraints and rate-independent ones which control them, whilst being minimally affected.

While Deacon’s autogen is not realistic from a chemical viewpoint, I don’t think this is a weakness. Far from it, it might be its greatest strength. The point seems to be to provide a general set of relations between constraints, irrespective of the nature of the constraints, and “sprinkle” some examples of these to make them clearer. There are of course other problems, some examples being: the heritability of the corresponding rate-independent constraints onto other autogen units (how to carry this out in a specific manner); if these constraints themselves are even stable enough to serve as inert memory structures, etc. But at least through what Deacon introduces, notions of naked-replicators are completely nonsensical. The point always is: what symbolic structures refer to must be something other than themselves, and always in the context of a system which uses this relation for its own benefit. And Pattee recognizes this [47]:

In any case, both categories of models seldom recognize von Neumann’s essential description-construction requirement that is essential for evolvable self-replication. Arguments over “information first” or “protein dynamics first” miss the crucial point. The symbol-to-action relation is inseparable. “It is useless to search for meaning in symbols without complementary knowledge of the dynamics being constrained by the symbols”.

However, Pattee regarding Deacon’s “offloading of constraints” writes [47]:

Deacon’s offloading is the inverse of the Central Dogma’s information flow from inactive one-dimensional sequences to three-dimensional active catalysts. Deacon’s offloading information flow is from three-dimensional active catalysts to one-dimensional inactive sequences.

To me, it’s unclear what this criticism is about, as (1) information flow is not uni-directional in a cell, (2) what Deacon says still seems to be about rate-independent constraints controlling rate-dependent ones, and (3) it being a reasonable representation of what von Neumann so early recognized, of the necessary separation between a dynamics and rate-independent constraints which control it, for a system to be evolvable in an open-ended manner (physical details are better contextualized by Pattee, von Neumann stressed the importance of separation between a description of a construction process and such construction).

Speaking of which…

Pattee makes great reference to von Neumann, particularly in this context with regards to his study of self-replicating automata [42, 63]. And with regards to this, Pattee very reasonably doesn’t at all seem to care about the “final result” which was a 29-state cellular automata (or the tesselation model), as through complete syntactization, it seems to hide and obfuscate the “most important part of the problem” (i.e. construction and how to physically embody the corresponding (symbolic) constraints). As von Neumann states [42]:

By axiomatizing automata in this manner one has thrown half the problem out the window, and it may be the more important half. One has resigned oneself not to explain how these parts are made up of real things, specifically, how these parts are made up of actual elementary particles, or even of higher chemical molecules. One does not ask the most intriguing, exciting, and important question of why the molecules or aggregates which in nature really occur in these parts are the sort of things they are, why they are essentially very large molecules in some cases but large aggregates in other cases.

What Pattee seems to care about is the physical realization of the abstract system that von Neumann generally described (kinematic model), and for which he (von Neumann) stressed the importance of differentiating between symbols representing software and symbols representing hardware, relative to our formal representations. Two notions, therefore, emerge out of von Neumann thinking about (self)replication, and I’ll argue that replication here should also be equated with replenishment or regeneration of constraints of a system without necessarily the creation of another system similar to the original one. These are copying by inspection or by description, that we’ve already seen a bit of before, with von Neumann arguing that copying by using a rate-independent (“quiescent”) passive description should be preferable over copying by inspection of rate-dependent (“reactive”) parts [p.122 42]. Needless to say, both of these are used by cells as we understand them. Pattee develops on what was said [43]:

The more fundamental question is how you make sure the replicated individual is like the original. How do you make a copy? There are two approaches. One is to copy the original parts themselves by inspection and then assembling the corresponding part in the copy. The other is to use a description of the original that when interpreted amounts to instructions enabling the assembly of the parts in the copy.

and

However, he did argue that a description had the advantage of being quiescent, relatively time-independent, and free of the dynamics of the system it describes. He saw that copying by direct inspection in real time would run into a problem with any dynamic part that was continually changing in time. What state would be copied in that case? He also suggested that a complete and detailed inspection, including inspecting the inspection components themselves, would probably lead to logical antinomies of self-reference.

These concepts themselves are very cognitively-biased, but the general idea is that in the context of copying or replicating something, inspection corresponds to a copy of the parts by physical interaction between the original and new parts without any use of interpretation, code, etc (e.g. by the use of an isomorphic relation - at molecular level we can think about shape-complementarity, etc); and description is copying based on interpretation. Both of these notions require a bit more elaboration, and I’ll do so by talking merely about constraints on a system, in no way referring to replication (i.e. originating a new system), as this capability of a system to self-constrain seems much more fundamental than replication itself (i.e. the “individual” in the previous quotes, or self, a system which can continually manufacture itself and have organizational closure, precedes replication; if there’s some set of constraints which after external or internally mediated disruption of the original system are “spilled” into the environment, and happen to be able to achieve organizational closure, then we say there has been (self)replication, but there’s always a need for an original system which has such closure).

If we look back at Deacon’s autogen, there were at least two different types of autogenesis: one which is mediated by a template onto which some part of the rate-dependent constraints are offloaded, and one which isn’t (simple autogenesis) being merely supported by rate-dependent ones. These are two reasonably different ways of preserving the disposition towards a target state, which is deemed by García-Valdecasas and Deacon as a hologenic constraint, as exemplified in the following figure [24]: